Dear friends,

Happy New Year! And oíche Shamhna shona duit!

November 1st is Samhain (pronounced “sow-in” in case you’re curious), the traditional beginning of the new year in Gaelic culture. It’s proceeded not only by Samhain Eve but also by … well, three days of drinking. And then followed by three days of regretting it, at least a little.

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and the onset of “the darker half” of the year, a time of increasing isolation and decreasing food stocks. It made all the sense in the world to do what people do in the face of adversity: throw a big communal gathering, feast, and dress up in scary costumes, and tell the agents of darkness to go elsewhere.

The Christian church, always on the lookout for a pagan holiday that they could cadge, imported it. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints. All Saints Day, or “All Hallows Day” in an older iteration, incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain in its All Hallows Eve festivities.

And so, I guess, a season of changes and a reminder that we best face adversity when we are shoulder-to-shoulder with our neighbors, hopeful and generous in spirit. (And spirits.)

In this month’s Mutual Fund Observer

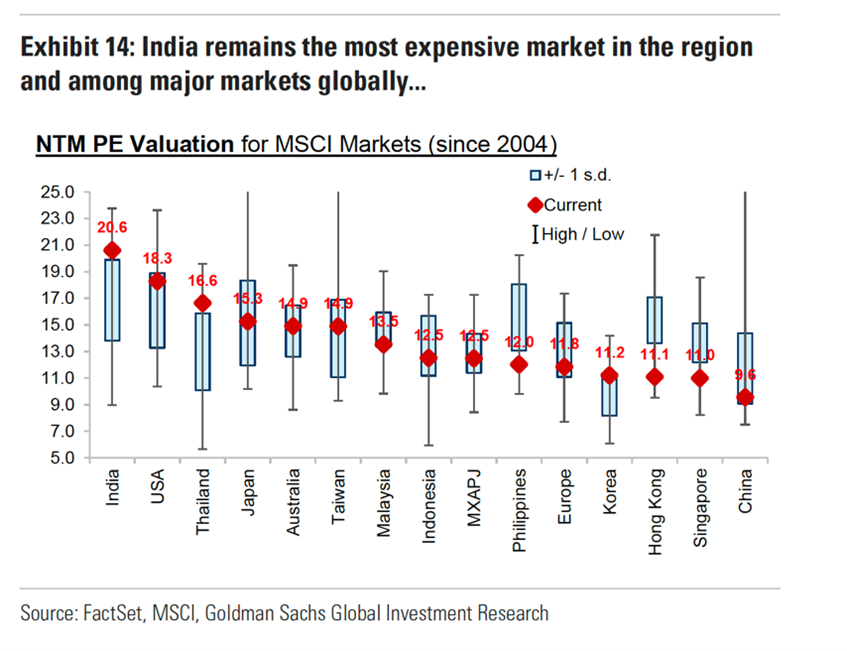

My colleague Devesh Shah shares another thoughtful report of a long luncheon conversation with Cohanzick’s David Sherman. Their talk is wide-ranging, touching on subjects from investing in India and MFO’s future to the foolishness of investment benchmarks. Part of the criticism there is driven by Mr. Sherman’s reading of a provocative essay by Howard Marks.

Howard Marks is the legendary co-founder and co-CEO of Oaktree Capital Management. I use “legendary” in recognition of two facts: (1) reportedly, his funds have returned 19% annually since inception, and (2) pretty much every grown-up in the industry takes Mr. Marks’ essays seriously. Oaktree invests $183 billion in “alternatives,” about two-thirds of which is invested in credit (sometimes called “high yield”) strategies. Their corporate philosophy centers on risk control, consistency of performance, and responsibility to stakeholders and to society. It is, on the whole, an admirable bunch.

Howard Marks’ essay to which Devesh and David Sherman refer, “Further Thoughts on Sea Change” (10/13/2023), makes two provocative arguments:

If the declining and/or ultra-low interest rates of the easy-money period aren’t going to be the rule in the years ahead … after a long period when everything was unusually easy in the world of investing, something closer to normalcy is likely to set in.

And …

Thanks to the changes over the last year and a half, investors today can get equity-like returns from investments in credit.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index has returned just over 10% per year for almost a century, and everyone’s very happy (10% a year for 100 years turns $1 into almost $14,000). Nowadays, the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Constrained Index offers a yield of over 8.5%, the CS Leveraged Loan Index offers roughly 10.0%, and private loans offer considerably more. In other words, expected pre-tax yields from non-investment grade debt investments now approach or exceed the historical returns from equity.

And, importantly, these are contractual returns.

By “contractual returns,” Mr. Marks means that absent a corporate default, if you hold one of these bonds to maturity, you will get your 10% per year. With stocks, contrarily, the best we can say is “if we hold stocks for at least 20 years, it’s pretty durn likely that the years of 50% declines and 70% gains will average out to around 10%. Probably.”

Mr. Marks, half facetiously, advised a non-profit on whose board he sits to “Sell off the big stocks, the small stocks, the value stocks, the growth stocks, the U.S. stocks, and the foreign stocks. Sell the private equity along with the public equity, the real estate, the hedge funds, and the venture capital.” The flip side is the perfectly serious observation that “if the developments I describe really constitute a sea change as I believe – fundamental, significant, and potentially long-lasting – credit instruments should probably represent a substantial portion of portfolios . . . perhaps the majority.” (The MFO discussion of the essay does flag the ugly risks inherent in owning high-yield if a recession strikes, fyi.)

I take Mr. Marks (and Mr. Sherman and Mr. Shah) seriously in “Investing Beyond The Great Distortion.” In that essay, I try to show both the empirical effects of The Great Distortion – the period of extraordinary events that Mr. Marks decries – and to highlight four funds that might make a material contribution to your portfolio in the market beyond it.

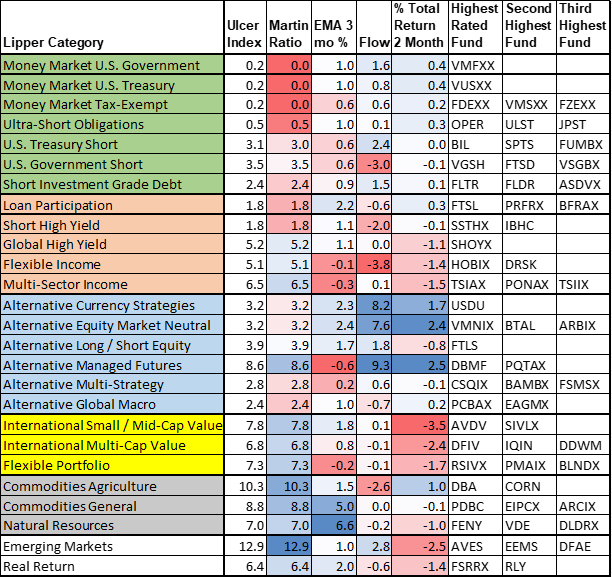

Lynn Bolin reflects on his adaptations of his own portfolio to some of the same forces in “Short Term Market Momentum.” Like others, Lynn is thinking about long-dated bonds as a potential source of capital appreciation rather than just income.

We also profile First Foundation Total Return, a fund nearly left for dead some years ago. Operating as Highland Total Return under a different adviser and burdened by at least two sets of bad inherited fixed-income holdings, the fund was staggering toward demise when First Foundation adopted it and revived it with great success. We share a bit of the story.

Finally, The Shadow does what The Shadow does, and shares three dozen changes – including three pieces of rare good news – in the industry. His Briefly Noted is well worth your time.

MFO neither engages in, nor particularly endorses, market-timing behavior. It’s a very good way to lose rather a lot of money. That said, the “sea change” argument advanced by Mr. Marks and others suggests an enduring, near-permanent change in the rules might be in the offing. We wanted to pair your consideration of that big-picture strategic possibility with a simultaneous change in the tactical situation. For that, we rely on the good folks at The Leuthold Group.

Leuthold: the lights have all turned red, time to lighten up on stocks

The Leuthold Group was originally a research provider to institutional and high-net-worth investors. The success of their research enterprise led them to begin managing money for rich people as a side business, and then to managing money for bright individual investors. Since investing is purely a mind game (a stock is worth what people believe it’s worth, a market rises when people believe it will rise … and act accordingly), they have identified and continuously tracked a huge variety of cues that have more or less greater predictive reliability when it comes to the economy and markets.

The Leuthold Group was originally a research provider to institutional and high-net-worth investors. The success of their research enterprise led them to begin managing money for rich people as a side business, and then to managing money for bright individual investors. Since investing is purely a mind game (a stock is worth what people believe it’s worth, a market rises when people believe it will rise … and act accordingly), they have identified and continuously tracked a huge variety of cues that have more or less greater predictive reliability when it comes to the economy and markets.

The snapshot is their Major Trend Index, which looks at changes in four broad aggregates: sentiment, valuations, technicals (e.g., trendlines or market breadth), and cyclicals (the behavior of assets that rise and fall with the rhythms of the economy and market). They say: “Major Trend Index is a weekly email update on the status of our 130+ factor assessment of stock market risk.”

In early October, it went broadly negative. By the third week of October, it became redder still as the Major Trend Index went “into the dumpster.” That decline caused Leuthold to “further reduce equity weightings in our tactical portfolios. In the Leuthold Core Fund, Core private accounts, and Leuthold Global Fund, equity hedges were adjusted to decrease net equity exposure to 44%.” (“MTI: Turned Negative, Trimming Equities Further,” 10/10/2023)

They’re pretty good at what they do. Their core product is Leuthold Core Investment, which is a five-star, Gold-rated tactical allocation fund. Neither allocation is 60/40, but they can drop stocks as low as 40%. Since its inception in 1995, they’ve made 7.8% APR; in every trailing period, they post higher returns than their peers (0.7-3.5% APR) with noticeably lower volatility. Their portfolio decisions are driven by the output of their quant models, not by their managers’ gut. On the whole, I would describe them as institutionally cautious.

In the last three months of decline, LCORX has lost 50% of what its peers have; over the past three years, it has made 250% of what they have (per Morningstar).

Here’s the LCORX homepage, which is moderately interesting.

The Season of Changes

Changes come, sought or not. We caught up with three people we greatly respect this month to become apprised of the changes in their lives.

Dan Wiener

Dan Wiener (celebrated by one of my senior colleagues as “Dan, Dan, the Vanguard Man”) began publishing The Independent Adviser for Vanguard Investors in 1991. It is the most widely read, cited, and respected of the publications focusing on the $8 trillion investment behemoth. Alongside that, he crafted a $15 billion investment advisory.

Dan Wiener (celebrated by one of my senior colleagues as “Dan, Dan, the Vanguard Man”) began publishing The Independent Adviser for Vanguard Investors in 1991. It is the most widely read, cited, and respected of the publications focusing on the $8 trillion investment behemoth. Alongside that, he crafted a $15 billion investment advisory.

A lot to cover for one guy … so he brought in one more. Then, sensibly enough, stepped back. We caught up with Dan on October 17th and poked him, just a bit, about his plans and his lessons from decades in the business.

On the next chapter:

We shall see what the next chapter brings. Right now I’m getting more involved with some of the private investments I’ve made (you could call them alternatives) in everything from energy to environmental safety to technology, plus a few food service businesses that have done amazingly well, contrary to popular belief. I also have plans to go skiing in Japan in February and take my son helicopter skiing in March. Plus, spend more time with my three grandkids.

On his advice for the readers we worry about most, the young folks just starting out and all the folks who are feeling strapped and uncertain:

My advice on investing for the young and uninitiated is the Nike advice, “Just do it!” But here’s the thing, no matter what anyone says about diversification or bonds, don’t listen. You want to go all in on stocks. Period. I have been investing since the 80s and even during the biggest bond bull market in history, you would have been a chump to have taken any money from stocks and put it into bonds. From December 1979 through December 2021, the Agg’s total return was 1,813%. The S&P 500 returned 13,162%. The Russell 2000 did 8,023%. The EAFE did 3,212%. So, even if you went all in on foreign stocks you still about doubled the return on bonds during a four decade bond bull market.

Anyway, a kid should do two things: 1, get in the habit of saving, and 2, buy stocks. I will leave it to you and your genius to tell them how to buy stocks. Me, I put my kids’ money into funds run by the PRIMECAP team and they did very, very well, thank you very much.

We celebrate the fact that Dan’s perspective on where best to invest is a bit at odds with the recommendations of other folks, who you’ll encounter below. That diversity of views is critical to your ability to sort through your own tolerance for risk and need for returns, in order to make the best decision for you and your family.

What do you know now that you wish you’d have known then?

As for what I wish I’d known 30 years ago, nothing immediately comes to mind. But two things do stand out. One is that luck and timing can help a lot. I was lucky to have come of age (professionally) when mutual funds were democratizing the markets. And as a journalist I had a front-row seat.

The one thing I would tell any youngster under your tutelage is that whatever they are into or whatever career they seek to pursue, to read, read, read. Immerse themselves in the industry, in the business, in the data of whatever they are doing. Become the expert. Stop playing video games and reading science fiction. Read trade journals. Read the WSJ. Read everything you can and talk to experts in the field. I think that’s one place where I was lucky as a journalist in that I had access to scores of publications and data and experts. (I never left the office without a briefcase full of stuff to read on my subway rides to and from home.)

Zeke Ashton

Zeke Ashton, founder, managing partner, and a portfolio manager of Centaur Capital Partners L.P., managed Centaur Total Return Fund from its inception. On November 1, 2018, the fund’s Board of Trustees announced an epochal change: Zeke, the last of its four founding managers, had notified the Board that he intended to resign after a run of 13.5 years. Before founding Centaur in 2002, he spent three years working for The Motley Fool, where he developed and produced investing seminars, subscription investing newsletters, and stock research reports, in addition to writing online investing articles. He graduated from Austin College, a good liberal arts college, in 1995 with degrees in Economics and German and subsequently has served on the college’s Board of Trustees.

Centaur was a remarkably good little fund. All-weather, great returns over time, absolute value orientation. Zeke wanted to have a fully invested equity portfolio but has kept 40-60% in cash since the market became richly valued. It’s made 12% annually over the decade because his stock picks perform really well; In 2017, he had a 13.5% return sitting on 50% cash, which means his stocks returned about 27%. We profiled it several times.

Zeke explained the decision to liquidate both the fund and its companion hedge fund as a decision about balance and meaning in life. “Being a professional investor takes so much effort, working weekends and nights. We’ve had no vacation in six years. We’ve been married for 14 years, running the strategy for 14 years. Business has come to dominate our relationship.” After chatting about family and health challenges, Zeke concluded, “This all made me realize, that the stock market is always going to be there, but the people you love won’t always be.”

This week, Zeke announced the decision to launch a hedge fund, Ashton Capital. (All the good names, he laments, were taken). Equity long/short, benchmark-free, and its historic total return emphasis. He promises “no crazy ARKK-like risks” but allows that he’s “too young to take no risks. We’ve been focusing on joy through this all, and I think that investing has brought the joy back.”

There is no plan to launch a mutual fund (too many headaches, too much competition), but RIAs and other qualified investors might follow his launch, and consider talking to the man himself.

Pierre Py

A short note on Pierre Py, one of the two founding managers of FPA International Value, which eventually (a) transitioned to a new advisor and a new name – Phaeacian Global Value and Phaeacian Accent International Value – and (b) famously crashed in a bitter business dispute between Mr. Py and his team on the one hand and the adviser, Polar Capital, on the other.

A short note on Pierre Py, one of the two founding managers of FPA International Value, which eventually (a) transitioned to a new advisor and a new name – Phaeacian Global Value and Phaeacian Accent International Value – and (b) famously crashed in a bitter business dispute between Mr. Py and his team on the one hand and the adviser, Polar Capital, on the other.

The dispute initially involved Polar Capital and FPA, but that piece has now been resolved.

The Polar/Py dispute has not yet reached a resolution, but he’s hopeful that the contest is much closer to its end than to its beginning.

In the interim, he and his long-time co-manager continue investing. For the moment, they continue managing the strategy through separately managed accounts. While the AUM is small, they have continued to add substantial alpha in 2022-23.

As we talked about the future, Pierre expressed a passionate desire to serve “the little guy.” He’s pretty openly critical of the direction that the investment industry has taken, producing “commoditized goods” driven by the demands of the marketing and distribution teams. The professional investors – the manufacturers, so to speak – have been devalued by years of relentlessly rising markets that seem to have convinced many that neither skill nor an appreciation of risk has any enduring value. “The investment industry gutted itself in favor of counting on rising markets; in a higher inflation and higher interest rate environment, that’s going to be really hard, and nearly impossible with a 200 name portfolio.”

We could, he notes, “have worked for a hedge fund or very rich individuals, but that’s not where our passion lies. I’m very keen to return to working on behalf of retail investors.”

We will keep an eye out and fingers crossed, both for Mr. Py’s sake and for yours.

JP Morgan: do yourself a favor, don’t overthink this one

An essay in the Financial Times argues in favor of radically simplifying one’s strategic asset allocation. It argues, at base, that unusual assets produce unusual returns only until they are discovered by the hoi polloi and the industry arbitrages away the exceptional gain. As a result, the real money is made by first movers, and the real costs are borne by those of us who try to get in later.

Here’s the core:

On average, research shows around 100 per cent of their total returns can be ascribed to their choice of policy benchmark [i.e., their strategic asset allocation], along with around 90 per cent of their return volatility. The outcomes of those judgments are often complex.

Jan Loeys, JPMorgan’s veteran asset allocation guru, says in a recent client note that this complexity is both pointless and counterproductive. Pointless, because investors need only two assets: a global equity one and a local bond one, with the relative amounts driven by their ability to withstand short-term drawdowns and return needs. (Less is more when it comes to strategic asset allocation,” FT.com, 10/17/2023)

There’s a really healthy discussion on the MFO discussion board that thinks through the implications of Mr. Loeys’ radical simplification. You might enjoy it.

Hard things done well

In 1983, John Osterweis founded Osterweis Capital Management to manage assets for individuals, families, endowments, and institutions. The firm, headquartered in San Francisco, manages $6.5 billion in assets and advises the Osterweis funds.

In general, Osterweis is distinguished in a number of ways. First, it detests the prospect of losing its shareholders’ money, especially needlessly. Second, it pursues strategies that don’t mesh well with Morningstar’s style-box-driven view of the world. Third, it’s very serious about doing good work for its shareholders. The fund is primarily employee-owned, and its management teams tend to be stable and loyal.

In general, Osterweis is distinguished in a number of ways. First, it detests the prospect of losing its shareholders’ money, especially needlessly. Second, it pursues strategies that don’t mesh well with Morningstar’s style-box-driven view of the world. Third, it’s very serious about doing good work for its shareholders. The fund is primarily employee-owned, and its management teams tend to be stable and loyal.

That makes it striking that the firm chose to liquidate three mutual funds in short order. The first two were the former Zeo funds. In October, they announced that Osterweis Total Return was following them to the graveyard. Curious, I reached out and was pleased by the opportunity to chat directly with Carl Kaufman, the #2 guy at Osterweis behind founder John Osterweis.

Here’s the short version of Carl’s explanation:

Most Osterweis fixed-income investing focuses on credit opportunities, not investment grade. That better credit offers a richer opportunity set, and the fate of a credit-driven portfolio is in the hands of the investors. An investment grade portfolio is subject to interest rate risk; as an example, Vanguard’s passive Long Term Bond ETF is down 44.5% since its peak in July 2020, at that’s through no fault of its own. Interest rates tick up, and long bonds die a bloody death. In general, that’s not a fight investors can win, and it’s not one that Osterweis – generally – wants any part of.

Total Return was the exception. Osterweis believed that they could construct an investment portfolio that would weather the market’s storms more than a portfolio with lower-rated bonds might. They found a good team, allocated resources to the fund, and stepped back and watched it for the past seven years. It started with two really solid years, then two okay years, and then the turbulence hit.

What they saw was disappointing. Mr. Kaufman somberly reports, “The fund was simply not serving its investors’ needs; it supposed to do much better in down markets than the typical bond aggregate fund. Heck, we thought it had a pretty good chance to go up last year. 2022 (when the fund lost 6.5%, a purely mediocre relative performance) was eye-opening. It had the promise, not the performance. It was time to react to reality. Really great team, but it is what it is.”

Mr. Kaufman commended to me a book that he’s been reading, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away (2022). The author is, among other things, a professional poker player and has studied cognitive psychology with funding from the National Science Foundation. As a culture, we worship persistence, from adages like “winners never quit, quitters never win” to celebrations of guys who pushed on through all the red lights to summit Mt. Everest (where they heroically, well, died).

Mr. Kaufman commended to me a book that he’s been reading, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away (2022). The author is, among other things, a professional poker player and has studied cognitive psychology with funding from the National Science Foundation. As a culture, we worship persistence, from adages like “winners never quit, quitters never win” to celebrations of guys who pushed on through all the red lights to summit Mt. Everest (where they heroically, well, died).

Ms. Duke argues that winning sometimes requires quitting:

Quitting, when done right, allows you to achieve your goals more quickly. This is counterintuitive, because we think of quitting as stopping our progress. But that’s not true when the thing you started isn’t worthwhile. If you quit, that frees up all of those resources to switch to something that will actually help.

I suggest creating what I call “kill criteria” in advance. Don’t trust yourself to do it in the moment. Ask yourself: what are the signals I could see in the future that would tell me that it’s time to quit?

Mr. Kaufman notes that Osterweis, effectively, has “kill criteria” for each of their strategies. They have expectations, criteria, and benchmarks for each strategy. They’ve got patience. And they’ve got a determination to end strategies that aren’t up to their standards. They closed their hedge funds in 2012 because of it, and they made the same painful decision with their three funds this fall.

Their decision strikes me as both rational and principled. And the conversation convinced me to pick up a copy of Quit from my local Barnes and Noble. (Amazon has proven to be so consistently predatory of its workers, suppliers, partners, and community that I’ve been trying to avoid them whenever possible.)

I’ll let you know what I learn.

Towle Deep Value Fund: what a difference 10 days can make

Towle Deep Value Fund is a deep value / small cap fund. It’s about the purest deep value play around, which is attractive because the academic research says that the “value effect” is most apparent in really deep value, just as the small-cap effect is most visible in really small caps.

Nice people doing hard stuff.

They’re currently a one-star fund in Morningstar’s system. Charles’s rating of them since inception (2011) is comparable: 1 (lowest 20% in the peer group based on risk-adjusted returns). This made their quarterly report pop, as they noted that their SMA composite for their strategy returned just over 19% annually for the past three years. Morningstar’s three-year numbers, which by default at the last 36 months from today, are far lower. Curious, I checked.

What a difference 10 days makes: the fund loses one-third of its trailing three-year returns when you shift from 9/30/23 as your end date to 10/13/2023. That’s about 10 trading days. But the opposite effect is seen in the five-year returns, which improve by 50%.

Three year returns (per Morningstar)

As of 9/30/23: 19.18%

As of 10/13/23: 12.74% – a 33% decline

Five year returns

As of 9/30/23: 2.47%

As of 10/13/23: 3.76% – a 50% rise

Ten year returns

As of 9/30/23: 6.43%

As of 10/13/23: 5.86% – a 10% decline

One reason that MFO traditionally pushed “full market cycles” as the metric rather than arbitrary windows (what is the significance of “three years”?) is that you need to find a way to avoid being misled by performance reports that might reflect one performance bubble rolling off just as a drawdown rolls on.

Which is to say: look long and hard (looking at you, Ms. Woods) before concluding, “those numbers are sweet! Here’s my money!”

Morningstar’s continuing weirdness

I received over 60 test emails from Morningstar “as part of my StockInvestor subscription,” over the course of two weeks. Nothing I did – including writing to media relations and retail support – stemmed the tide.

(I don’t even subscribe to StockInvestor.) In the face of all of that, the eventual response was almost laughable.

Hello David,

We hope you are doing well.

We would like to inform you that the team responded to us that they were not sending any emails but they will be cautious for any future reference.

Best regards,

_________________________________

Morningstar Global Product Support

“They are not sending any emails”? Ummm … yes, they were.

If you’re seeking a really good reason to support an alternative to Morningstar, quite apart from the abandonment of retail fund investors, dominance of AI-written text, and mindless fund screener, that might be it.

Thanks

To The Faithful Few, whose monthly contributions keep spirits up and the lights on: S & F Investment Advisers, Wilson, Brian, Gregory, Doug, David, William, and William. If you’d like to do your part to keep MFO up and running, please click on the “Support Us” link above or join the MFO Premium folks who, for just $120/year, get access to maestro Charles and some of the most advanced search tools available (or, at least, “available for less than the $16,000 that some others charge”).

Cheers!